A comparison of the notion of transcendental participation and that of maternal generation in the double perspective of essential Thomism and the phenomenological analysis of archetypically maternal aspect of divinity.

K. Smykova

Abstract

The article offers a comparison between the metaphysical notion of transcendental participation of all the created beings to the Being of God as exposed by Cornelio Fabro and the notion of maternal generation in the perspective of phenomenology of archetypes elaborated by Erich Neumann. The objective is to contribute to the ontological foundation of the metaphors of God’s motherhood elaborated in light of the feminine archetype.

I understand three ways of contemplating motherhood in God. The first is the foundation of our nature’s creation; the second is his taking of our nature, where the motherhood of grace begins; the third is the motherhood at work . . . and it is all one love.[1]

Julian of Norwich († after 1416)

The motherhood of God is not a concept foreign to the Bible, nor to the Church tradition. The Bible knows the metaphors that describe God as a mother, using images taken from the archetypically feminine semiotic field.

The human soul is compared to the “like a weaned child is my soul within me”.[2]; through the mouth of the prophet Isaiah God explains the nature of his attitude of tenderness towards man by resembling his mother. As the woman does not forget her child, but she comforts[3] and takes care of it, so is the Lord and even more: “Can a woman forget her nursing child, or show no compassion for the child of her womb? Even these may forget, yet I will not forget you.”[4]

The ingratitude pushed to the point of betrayal of the covenant becomes the occasion for the manifestation of the other side of the analogous maternal aspect of God, who shows himself ready to “devour” with the ferocity of a lioness and attack like a she-bear deprived of her children, in order to break” the covering of their heart ” of her rebellious children.[5]

God “cries out like a woman in labor”[6] and comforts “like a mother”,[7] his plans are compared with the womb, and the creative impulse with birth.[8]

In the NT Christ recalls the female image of divine care for his people: How often have I desired to gather your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you were not willing! [9]

The references to the motherhood of God are known in the tradition as well, where the maternity of God seems to be systematically linked either to the second of the third Persons of the Trinity.

St. Bede compares the Virgin Mary to the Holy Spirit: “The Mother of God herself receives the grace by which we are saved, – the Jews also have a spirit that gives virtue of a feminine kind”. [10]St. Augustine says of the Holy Spirit: “as eggs are warmed by birds, when the warmth of the mother’s body, combined with her love, promotes the formation of chicks…”[11]

Medieval piety, especially that developed in the 13th and 14th centuries, offers devotion to Jesus as mother. By analogy, feminine virtues attributed in the Middle Ages to Christ, are being transferred to the figures of abbots, bishops, apostles: male religious authorities who assumed upon themselves the ministry of pastoral care and of “nourishment” of the faithful.[12]

As we see, there are different approaches to the femininity and the motherhood of God. It is certainly present in the Bible and in Tradition, even if largely overshadowed by male metaphors.

What is the reason for this?

Anselm of Canterbury in Monologion argues that God should not be called Mother because a male occupies a higher role in the reproductive process of a child. The father is the one who elaborates the form, the being of the child and the mother is the one who cares and provides affection. [13]

As we see, the reason given by Anselm is partly cultural and dependent on the limited knowledge of biology of his time. However, it is important to note that in its structure this argument is ontological: woman does not generate. The nature of female is such that the authentically active role in creation itself cannot be attributed to her.

Woman comes second in order of creation, she helps procreate, receiving the seed of life, nourishing it and making it grow, but she does not create as the male does. She plays a crucial role in everything that has to do with upbringing and taking care of the child. This can possibly be an explanation why Christ as nourishing the Church and the Holy Spirit in the role of a gardener of souls and comforter can both be called “mothers”, while God in his creative aspect is less likely to be. In fact, God generates his creation and gives it form, while a human mother doesn’t.

In this article we want to tackle the question of ontological foundation of the metaphors of the motherhood of God in its generative and creative aspect.

To achieve this, we will compare two perspectives. The perspective of essential Thomism as presented by Cornelio Fabro and the perspective of the phenomenological analysis of configurations of maternal divinity in work Erich Neumann.

At the end of the article, we will give an example of such a dual-foundation analogy. Virgin Mary can be taken as a symbol of eternal generation.

We should start with the question indispensable for understanding the thought of Neumann.

What is archetype?

The term ‘archetype’ itself is composed of two elements: ‘arche’ meaning ‘beginning, principle, origin’ and ‘typos’ that refers to ‘imprint, mold, matrix, image’.

The term archetype was coined by Jung to indicate that the collective unconscious shares an image that functions as “the native ground of every conscious psychic event”.[14] This original ‘matrix’, even though not possessing any specified content, influences the way of development of the individual conscience. The archetype, writes Jung, is “quod semper, quod ubique, quod ab omnibus creditor”: what is always believed everywhere, by all.[15]

It can be said of the archetype, according to Neumann, that it presents itself as a mythological motif contained ‘eternally present’ in the collective unconscious. For Neumann, ‘collective unconscious’ stands for ‘what is universally human’. Being universally human, this motif expressed in symbols of various degree of complexity and development (from Upper Paleolithic Venus to modern philosophical systems[16]) reappears in different cultures and religions. It can appear both in Egyptian theology, both in the mysteries of Mithras, and in Christian symbolism.[17] It will be true to say that in this article we are primarily concerned with Christian context only.

In his famous work The Great Mother (1956) E. Neumann, attempting to clarify the structure of the archetype, defines it as an “inner image that acts in the human psyche”, a “psychic phenomenon” characterized by emotional and symbolic components.

The bulk of the human being’s experience occurs in the unconscious. The archetype, as the bearer of this unconscious experience, can only be perceived by consciousness – and therefore be analyzed and reflected upon – only when it takes on a form. In other words, when it manifests itself in specific psychic images. Although acting in the unconscious, it becomes visible to consciousness at the symbol level. For this reason, the methodology of the study of the archetype is primarily phenomenological. If we want to compare the configurations that the archetype assumes in the psyche, we need to study the ‘effects’ of this archetype, to study, so to say, its shadows projected unto particular manifestations of human culture.

Each archetype has its own ‘symbolic canon’, that is, the range of symbols with which the archetype expresses itself. In other words, it can be said that these symbols “belong” to the archetype. For example, the vase, the tree, the ship are all images belonging to the Archetype of the Feminine or the Great Mother. It should be specified here that the Great Mother is only one of the ramifications of the feminine archetype, presenting the feminine primarily under the aspect of creation and generation – precisely, the aspect that interests us.

There is an element of mystery in the nature of the archetype itself. The archetypal content – the symbol – always expresses – and can only express – similarity or an analogical or metaphorical[18]relationship, but the archetype itself remains for us “fatally unknown and indefinable”.[19]

As Neumann points out, it is difficult to describe a single archetype. There is no way to dissect the psyche, isolate an archetype and break it down into constituent parts. The archetypes interpenetrate, they exist in a state of mutual fusion, with an intertwined symbolic polyvalence.

The character of the Female Archetype

Similarly in the case of the archetype of the mother there exists a symbolic polyvalence, a vast number of shapes, images, symbols pertinent to the dynamics, (the activity, the effects) of the archetype.

At the base of both generically diversified archetypes (the Great Mother and the Great Father) we find a “uroboric totality”, that is, the symbol of the inextricability of chaos, of the unconscious, of the totality of the psyche. The Ouroboros or “the Great Circle”, represented as the snake that bites its own tail, contains fused male and female elements. It is the symbol of the original situation, in which primitive man lives. In this external and internal situation of the psyche, world and man, power and things exist as a whole, an indissoluble unity.

The Archetype of the Feminine emerges from the Ouroboros and presents itself as the same Great Circle defined by two characters: elementary and transformative.

In its elementary character, this archetype is expressed through offering protection, nourishing, warmth and is inextricably connected with the state of dependence. The individual – both male or female – experiences the relationship with the female archetype under elementary character as lacking in autonomy, infantile. For this reason, the elementary character almost always has a maternal determinant. It is the most basic expression of the Great Mother.

The peculiarity or the Archetype of the Great Mother

Here we need to introduce fully a rather long quote from the Neumann’s book, not to distort the precision with which this thought is formulated:

We define elementary character as the appearance of the feminine which tends, as a ‘Great Circle’, a large container, to hold still what arises from it and to surround it as an eternal substance. Everything that arises from the feminine belongs to it, remains subject to it and, even when the individual becomes autonomous, the Feminine Archetype relativizes this autonomy, making it a secondary variant of its eternal essence. [20]

Anticipating what is still to be said about the notion of God (the Absolute Being) in Fabro-Aquinas, we want to underline the aspect of the relativity of autonomy. The individual which receives its being from the Great Mother, carried its nature in one’s own, continuing to be connected to it because of the impossibility to turn anywhere where it is not – in fact, its nature is eternal and all-surrounding, all-embracing.

It is experienced as a numinous omnipotent Feminine reality. By experience we mean what consciousness experiences as a transpersonal, indeterminate, omnipotent and divine force.

For primitive man, as for the child, for whom the world is experienced ‘mythologically’, the mother is the first and closest analogy of God as the great omnipotent force, she the source of the basic numinous experience of absolute dependence. “Nowhere as in the mother, perhaps, is it so evident that a human being can be experienced as great”. [21]

This is the elementary character of the Feminine. What is emphasized here is the dependence of who is generated and the aspect of containment. It is, so to say, “conservative” side of the archetype.

The quintessential symbolism of this aspect of the Great Mother is the vase.

The feminine is experienced as the vase: the container of life, in which life is formed, which generates every living thing, generating it out of itself and towards the world. The sea, the ocean, the lake, the water are the elements that naturally follow the symbol of the vase. The containing water is understood as the primordial womb of life.

But the picture would not be complete without the archetype’s other character, the transformative one.

The transformation takes place within the Great Circle, in it and for it.[22] Maternal water not only contains, but nourishes and transforms, since every living element elaborates and preserves its essence through the water that keeps it alive.

Neumann argues with the patriarchal conception which affirms “the victory of the masculine rests on the spiritual principle” that devalues the moon, as well as the Feminine to which it symbolically belongs, and makes the transforming feminine character a specifically material aspect, dependent on the sun as spirit. In other words, the feminine archetype would represent the ontological situation we started off with in the introduction.

By reconsidering the patriarchal conception, Neumann suggests that the transforming spirituality of the archetype of the Great Mother should be recovered:

The mystery of transformation is the product of the Great Circle as its luminous essence, its fruit, its son. The spirit does not emerge as an Apollonian, solar, patriarchal conception, as a being in itself, as a pure, absolutely eternal existence, but remains ‘filial’, understanding itself as endowed with a historical origin, as a creature.[23]

Furthermore, he analyzes how mysteries of transformation related to the blood demonstrate that the Archetype of the Great Mother, in its basic conception, is not dependent, but active and even independent in its generative role. In fact, the role of the generation seems to have belonged to it alone:

According to the concession of the primitives, the embryo is processed from the mother’s blood, whose emission, as evidenced by the interruption in menstruation, ceases during the period of pregnancy. The feminine experiences in pregnancy a combination of elementary and transforming character.[24]

Taken into consideration together the two characters present the broadest phenomenology of the Feminine Archetype. It embraces and contains the entire Universe, where everything receives its existence from the Great Mother and participates in her life. The life she gives is both the transformation and the containment of the transformation. The elementary character hides both what is being transformed and what has been transformed in its circle.[25] [see ‘Table 1’ in the attachment for comparative imagery].

Participation in Fabro-Aquinas.

The peculiarity of Aquinas metaphysical conception of being, as offered by Cornelio Fabro.

Having concluded the presentation of the first phenomenological part, in which we have outlined the conceptual foundation of participation of being in the life of the Archetype of the Great Mother, we now begin the second part of our discourse. This will be dedicated to Thomistic metaphysics in the interpretation of Cornelio Fabro, who was able to detect the importance of the notion of transcendental participation and the developed notion of being (esse) in the work of Aquinas.[26]

Now we have come to the most technical part of our text, which may require some familiarity with philosophical terminology on the part of the Reader.

We will try not to go into detail, but we do need to outline the essence of the idea of transcendental participation in order to convey the analogical similarities between the two perspectives.

Fabro’s philosophical thought is profoundly Thomistic, but it is not medieval.[27]

Its peculiarity consists in that it’s a Thomism that does not align with other interpretations of Aquinas’ thought that often tend to interpret him as the ‘baptized Aristotle’. He showed how in the works of the Angelic Doctor Aristotle and Plato do not stand in opposition, but rather coexist in the higher synthesis, which means that the resulting thought brings something radically new.

Fabro understood that the permanent presence of the term ‘participation’ in the texts of St. Thomas hardly relates to what was imagined as the organic elaboration of Aristotelian thought. Indeed, Aristotle was highly critical of the Platonic notion of participation.[28] Yet, Fabro discovered, the term is recurring in Aquinas.

As is known, the pivot of Aquinas’ metaphysics is the fundamental distinction between id quod est et suum esse: between the entity (the essence that actually exists in individual form) and its being. Esse, however, in the way it is elaborated by the Doctor, acquired a novel meaning that doesn’t find comparison in all Western thought. “Compared to previous authors, St. Thomas brings about a recovery of the absolute emergence of esse, as a result of the Aristotelian metaphysics of the act within which the Platonic notion of participation is being incorporated and profoundly modified”.[29]

The ontological and metaphysical thought presented by Fabro is, obviously, not a classic theistic metaphysics, placed on the line of Aristotle’s thought, but neither is it Aquinas of the presumed distinction of essence and existence.

St. Thomas’ esse is not simply the synonym of ens[30], as it happens in common language, and it is neither a synonym of existere, that is, the mere fact of being real, of ‘finding oneself in the state of being’. Esse for Aquinas is none of that, but it is actualitas omnium actuum: the actuality of all acts[31]. The being in act (esse in actu) of the ens is the result of the composition of two acts. Two deeper, original acts, namely the form and the cause (essence and participation in ipsum esse). [32]The ‘modes’ of being of the Creator and the creation therefore can be determined as ens per essentiam (that which has being in itself) and ens per partecipationem, each having their own ontological quality. The former one being absolutely simple (= absolutely perfect, not composed, not admitting any change within itself), the latter one resulting as a composed being.

For the convenience of the exposition of Fabro-Tommaso’s core idea, we’ll provide here a brief metaphysical synthesis to explain in some key points the logical passage with which we arrived to the notion of participation of essences to ipsum esse.

1) As with every [Western] metaphysical discourse, we cannot avoid beginning with the basic Parmenidean principle: being is and cannot not be; non-being is not and cannot be. Therefore, being in itself is eternal, stable and cannot pass into non-being; it is reality at the highest degree, a plexus of all completeness or perfection and is therefore the most perfect and complete of all. This is the principle of non-contradiction: it demonstrates the eternity of ipsum esse that, therefore, is subsistent (self-sufficient, self-supported) and not being ‘limited’ (because otherwise there would enter a non-being) it is therefore infinite.

2) The essence of any truly existing entity is made up of potency and act. In the case of material beings, potency equals matter and act equals form (in more detail, see below n.8 and n.9 of the present synthesis).

3) Every actually existing entity is made up of essence and being (esse).

4) The essence contracts ipsum esse (being itself, pure being) to a determined ‘way’ or ‘mode’ of being.

5) The effect, the result of this determination is the entity or primary substance or individual entity.

6) The causes of this determination[33] are the ‘formal’ causes and they are immaterial and transcendent the matter and therefore cannot be reduced to the matter (materia).

7) What is being determined (by essence as an effect of formal causes) is a matter, shapeless and empty, the abyss of Genesis.[34] It receives its individuality, its limits from the form.

8) The form is called the first act. This type of form is called substantial, it is the constitutive principle of the essence; there is also the accidental form that indicates the occurrence of a certain property in a substance, such property is not crucial for the identity of the composed ens. Such properties are, for instance, weight, height, length, color, etc. Thus, we can distinguish the essential properties that give essential identity to an ens, to an individual being. For a human being such property is being an animal and therefore a living being with the peculiarity of being endowed with intellect and will. The ‘animal’ or ‘living being’ are generic properties; human being is the species, that has intelligence as its peculiar specific differences.

9) Form is the principle of the act (= determined esse) and matter is the principle of potency (= indeterminate esse) even if they do not exist in themselves but only as causes or ‘that by which something (= esse) exists according to the determined measure of its essence (= the way in which being is contracted)’.

10) What exists, on the other hand, is the primary substance or ens which is the subject of causality.

11) Now, since the ens is subject to non-being (the corruption of its form; when the form is corrupted, follows the end of its existence) it cannot be the ‘being that is and cannot not be’ (ipsum esse), because in fact it ceases to exist (it is therefore called contingent); this is the reason why esse which is eternal, the perfect one among the perfect ones, is the absolute foundation and origin of ens.

The being of the ens in fact ‘participates’ in the only act of being (actus essendi) whose foundation ‘can’ make the ens exist in actuality, because ipsum esse is more than substance – it is the supreme subsistent act and therefore the necessary foundation of any other act of being.

12) Act is energy, perfection and completeness; there is nothing more complete than esse: it is like a light that is eternally illuminates the entity in the actual or potential state and causes its existence.

13) To obtain the best understanding it is important that we specify this one point: the transcendence of esse is the immutability of the eternal which, being immutable, changes[35]without passing into non-being – because esse is eternal, incorruptible, motionless, ungenerated and infinite, it is pure, ‘strong’ actuality and is the utmost presence, the utmost greatness and absolute foundation of the existence of all the different, multiple, interrelated, unique and singular entities that are called entities because they are ‘modes’ of being (they are determined and limited by their essence, their nature generically and specifically), modes that are ‘formally determined’ to participate in esse according to different and ascending degrees of perfection. Being the Esse of ens and Cause of every cause – it is more than an ordering principle of being (like Demiurge) but it is itself the cause of ‘existence as order’. Therefore, everything participates in the eternity of Esse according to various generic and specific degrees of formal perfection.

14) God is Esse as transcendental synthesis or self-synthesis or the unity of himself as supreme being (whose essence is his very act of being) and of creation as being participated in his supreme reality. In fact, esse of the supreme and infinite being and esse of the finite being are analogous (ens per essentiam and ens per participationem).[36]

Here ends the synthesis because we have reached the core idea of the transcendental participation.

The participation in esse, or the transcendental participation or vertical participation is what is called the metaphysical causality. It is this type of causality that Aquinas keeps in mind when he uses the term ‘First Cause’ speaking of Subsistent Being. Fabro’s merit was to discover this original core in the notion of ipsum esse (the Supreme Being, or God for believers) as an intensive act. This notion was achieved through the notion of participation.

Individual beings participate in Ipsum Esse according to the diversity of their essences or natures. The essence of each entity will therefore relate to esse as potency relates to act. Only in the Subsistent Being essentia coincides with esse, for it is Pure Act without any potentiality. [37]

Transcendental participation is a relationship, archetypically very close to the maternal Ouroboros. The uncaused Universal Cause transcends the cosmos of contingent entities and, regardless of time (it is eternal), is participated in by all created entities and preserves the being of each one of them and of their causally ordered whole (on the immanent physical level of their being, so called predicamental participation).

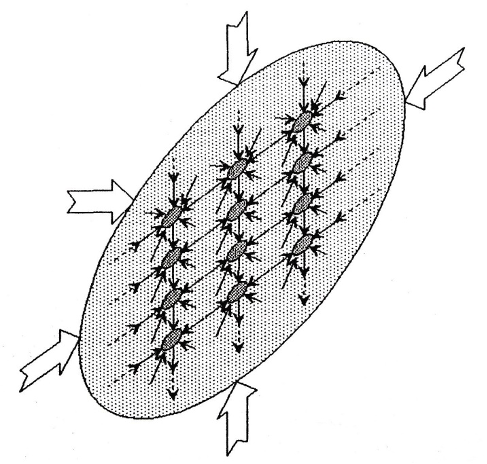

Here we use figure 5-3 from the book by G. Basti [Basti, 2002] as it excellently visualizes the inter-relationship “between the Metaphysical First Cause (large arrows), that is ‘found’ outside the space-time universe (large clear circle), and physical secondary causes (small arrows) within this universe which concur to determine (on a causal level different from the First Cause, as symbolized in the drawing by the fact that the secondary causes occupy two dimensions, the Cause occupies three dimensions) the existence (the content) and the essence (the outline) of the being of the single entities (small darker circles). The esse of every entity, essence and their ‘being an entity’ and their existence, therefore consists in the result of the causal concurrence of the First Cause and the secondary causes”. [38]

It is therefore a relationship of preservation of each and of the totality, founded on the principle (the Supreme Being as First Cause) different from the totality itself. [39]

For Aquinas, esse is the first absolute metaphysical value. He wanted to avoid it being interpreted as one act among many, one substance among many. [40] Different from the Neo-Platonists thought that presents esse as created. [41]

God is Esse as a transcendental synthesis (or self-synthesis or the unity) of itself as a ipsum esse(whose essence is its very act of being) and of the creation as participating in its supreme reality.

In other words, the change, the passage from being formed in a certain way (with its mode of being) to being formed in another (die to the concurrence of the secondary causes), implies the necessary foundation in the eternal, incorruptible and stable being, whose stability is the foundation of its own incessant change.

The final conclusion in the exposition of this second perspective is that God is esse as the relationship between the transcendent (static) self and the immanent (dynamic) self. The transcendental unity of the two as it coincides with this relationship is what we call divinity.

An example of the double metaphysical-phenomenological foundation of a Christian analogy

In this last part of our essay, having outlined the two perspectives on the generative nature of God and the analogical language that we use to describe it, we will try in the way of experiment to bring these two together in the example of an actual analogy in Christian context.

We therefore suggest this Mariological reflection as the synthesis of everything that has been said so far. We hope that with this we can give an example of what an ontological foundation of the metaphor of the Motherhood of God.

The intuition of the Absolute that our psyche conveys through the unconscious must take on a symbolic content in order to be processed. An archetype remains concealed because it is the foundation of all of its individual projections. Similarly, God, being the Supreme Being, cannot be ‘seen”, because of his utmost intimacy with the individual beings who participate in its Being.

This is why Jesus says “Whoever has seen me has seen the Father. How can you say, ‘Show us the Father’? Do you not believe that I am in the Father and the Father is in me?” [42]Indeed, the only way we can relate to God consciously is through having a personal relationship with him, which was rendered possible by his ‘self-contraction’ to a determined individual.

If we ask ourselves “what does it mean to ‘see Jesus’?”, we will understand that this relationship of seeing and knowing is itself dynamic, of a nature different from the nature of a static image, akin to a portrait or a photograph. It requires, in fact, an inner work from us, our involvement. ‘Seeing’ is a dynamic process, which involves the whole human nature in Christ.

Therefore, if the whole human-divine person of Christ is the subject of our ‘dynamic contemplation’, we cannot omit the relationship of sonship in the historical Jesus. This sonship, with its components involved (the conception, the formation in the Mary’s womb and the birth of the Logos in human flesh) opens up a vision of God, of the Father through the analogy of generation that we find in the Blessed Virgin.

The famous paradoxical formula found in Dante’s Paradise: “Virgin mother, daughter of your Son””[43] it is the best symbolic synthesis of Aquinas’ metaphysics of the participation of being.

The reason is because it prodigiously summarizes the idea that the nature of being is an effect of the expansion of Being according to its contracting to a specific formal degree of Itself.

God takes on himself a substantiated spiritual form that is being determined in his mother’s womb. Ipsum Esse Subsistens is determined to a formal degree of perfection of himself, the most perfect and complete of all created beings: Jesus the Nazarene, with his unique “double” nature, divine and human.

By double nature, following to the reading of Fabro-Tommaso, we intend the ‘transcendental composition’ of the eternal, intensive, absolute being on the one hand, and of the determined being, the being of the entity on the other.

“When the fullness of time had come, God sent his Son, born of a woman”.[44]

If Mary is the Mother of God, it implies a relationship between her and God, more precisely between her and the divine person of the Word-Logos-Son of God. The foundation of this relationship is the generative act of Mary in regards to Jesus, the Incarnate Word.

The contribution of parents in ordinary case of generation involves a secondary cause of creation the concurrence of both parents for the formation of the body.

In the case of the divine transcendental generation of the Son, there is the miracle of the virginal conception.

With this miracle, God makes it possible that the generative action of the woman, whose nature is partial, unable to produce that effect of a new living being, alone produces the initial cell of the new organism. In the very instant of the formation of this cell, the creation of the soul takes place, and with this the constitution of the totality of the new human being by God.

Mary is therefore the mother and the only human parent of the new being who is Jesus; and she is therefore the mother of the Word, since this man is the Word in his essential form.

The divine-humanity of Jesus Christ is formed by the double causal concurrence of the transcendental participation in the Being of the finite form of its own Word made flesh in Jesus, who is truly human, having had the secondary cause of his human nature in the natural generative action of Mary, who was not ‘fertilized’ by a male seed, but the generation occurs in which the virgin “secretes” the divine form that has been actualized in her womb, completely independent of usual natural reproductive factors.

The paradox of Mary is that she is Mother of the Creator, however, she is created by the Creator himself in order to generate Him. The relationship of divine maternity is a real relationship in Mary. The fact that she has become the Mother of the Word adds something to her, gives her a perfection that she did not have before that.

In the case of Mary, the humanity of Jesus has a unique origin in her, just as the divinity of God has ‘origin’ only in himself, in the Trinitarian relationship.

By virtue of this motherhood, a singular analogical similarity with the first Person of the Trinity was achieved in the Blessed Virgin.

As, in fact, the Father generates the Word from eternity according to divine nature, so Mary generated him in time according to human nature. As the Father generates him from his divine substance, so the Mother generates him from her human nature. Just as the Word is the only Son of the Father, generated by him virginally (that is, without any external input), so too the only son of the Mother is virginally generated by her.

In the words of St. Anselm: “the Son was naturally one and the same common Son of God the Father and of the Virgin”. [45]

Having no intention to deny the actual fact of the virginal conception, we can nonetheless argue, that it can also be seen as an archetypical projection and in this case the unique generation is a projection of the maternal archetype disguised as a paternal one (Father). The Feminine in its character of the Great Mother bears the ‘virginal’ creative principle as one of its important characteristics.

This, [46]in our mind, constitutes a strong enough foundation for the legitimacy of the metaphors of motherhood of God in the aspect of divine generation.

Bibliography

Abbreviations

S.Th.: Somma di Teologia.

NRSV.: New Revised Standard Version

Books

Gianfranco Basti, Filosofia della Natura e della Scienza – I, Lateran University Press, Città del Vaticano, 2002.

Carolyne Walker Bynum, Jesus as Mother. Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle Ages, University of California Press, Ltd., London, 1982.

Tommaso D’Aquino, Somma di Teologia, ed. F. Fiorentino, Città Nuova, Roma, 2018.

Christian Ferraro, Cornelio Fabro, Lateran University Press, Città del Vaticano, 2012.

Christian Ferraro, La svolta metafisica di San Tommaso, Lateran University Press, Città del Vaticano, 2014.

Erich Neumann, La Grande Madre. Fenomenologia delle configurazioni femminili dell’inconscio, Casa Editrice Astrolabio, 1981.

Articles and miscellaneous

St.Anselm, De conceptu virginali et de originali peccato, J. Hopkins, H. Richardson (ed.), The Arthur J. Banning Press, Minneapolis, 2000

St Augustine of Hippo, Opera omnia. Vol 2. On Genesis, Aleteia, Saint-Petersburg, 2000.

Andreas Fingrnagel, Christian Gastgeber (ed.) The Book of Bibles, Taschen Bibliotheca Universalis, Cologne, 2016.

C. G. Jung, Psychologie und Religion, Gesammelte Werke, Patmos-Walter, Düsseldorf, 2011 (Walter, Olten-Freiburg., 1966-1994).

Electronic Resources

Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy, Paradise. Digital Dante: https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/paradiso/paradiso-33/ [Accessed 17.07.21]

St. Bede, Commentary on the Books of the Old and New Testaments. On Proverbs. Azbuka Very: https://azbyka.ru/otechnik/Beda_Dostopochtennyj/tolkovanija-na-knigi-vethogo-i-novogo-zaveta/#0_4[Accessed 04.07.21]

Julian of Norwich, The revelations of the Divine Love, Christian Classics Ethereal Library:https://www.ccel.org/ccel/julian/revelations.html [Accessed 17.07.21.]

New Revised Standard Version, Bible Gateway: https://www.biblegateway.com/versions/New-Revised-Standard-Version-NRSV-Bible/#booklist [Accessed 17.07.21].

Attachments

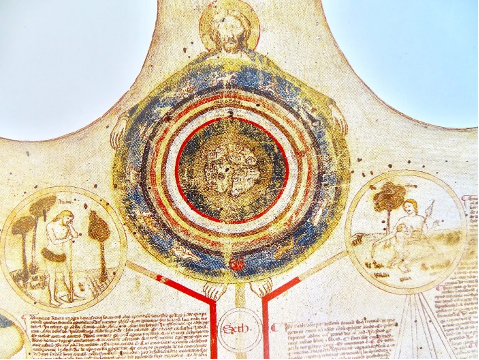

Table 1. Comparative images of Virgin Mary with Christ and God the Creator.

Image 1. [photo from private collection, 2021] A Byzantine fresco depicting the Madonna and child (7th– 8thcentury). The Basilica of Santa Sabina, Rome. The Blessed Virgin, by virtue of her divine motherhood, achieved a singular analogical similarity with the first Person of the Trinity. |  Image 2. [Taschen, 2016] God as the Creator of the world. Bibles moralisées, Paris, 13th century. Cod. 1179, fol. 1v (Genesis).  Image 3. [Taschen, 2016] The Creator with a representation of the world composed of concentric circles. Below left and right: Adam and Eve. Genealogy of Christ, Upper Italy, 15thcentury. |

Table 2. Comparison of the key concepts.

| Phenomenological Perspective on the Archetype of the Great Mother | Perspective of Essential Thomism on the participation of entities to the Absolute Being |

| We define elementary character as the appearance of the feminine which tends, as a ‘Great Circle’, a large container, to hold still what arises from it and to surround it as an eternal substance. Everything that arises from the feminine belongs to it, remains subject to it and, even when the individual becomes autonomous, the Feminine Archetype relativizes this autonomy, making it a secondary variant of its eternal essence.[47] | God is Esse as transcendental synthesis or self-synthesis or the unity of himself as supreme being (whose essence is his very act of being) and of creation as being participated in his supreme reality. In fact, esse of the supreme and infinite being and esse of the finite being are analogous (ens per essentiam and ens per participationem). [48] |

| Maternal water not only contains, but nourishes and transforms, since every living element elaborates and preserves its essence through the water that keeps it alive. | The uncaused Universal Cause transcends the cosmos of contingent entities and, regardless of time (it is eternal), is participated in by all created entities and preserves the being of each one of them and of their causally ordered whole (on the immanent physical level of their being, so called predicamental participation). |

| The life she gives is both the transformation and the containment of the transformation. The elementary character hides both what is being transformed and what has been transformed in its circle.[49] | To obtain the best understanding it is important that we specify this one point: the transcendence of esse is the immutability of the eternal which, being immutable, changes[50] without passing into non-being – because esse is eternal, incorruptible, motionless, ungenerated and infinite, it is pure, ‘strong’ actuality and is the utmost presence, the utmost greatness and absolute foundation of the existence of all the different, multiple, interrelated, unique andsingular entities that are called entities because they are ‘modes’ of being (they are determined and limited by their essence, their nature generically and specifically), modes that are ‘formally determined’ to participate in esseaccording to different and ascending degrees of perfection. Being the Esse of ens and Cause of every cause – it is more than an ordering principle of being (like Demiurge) but it is itself the cause of ‘existence as order’. Therefore, everything participates in the eternity of Esse according to various generic and specific degrees of formal perfection. |

[1] Julian of Norwich, The revelations of the Divine Love, LIX, 146.

[2] Psalm 131, 2: NRSV (same for all Bible quotations).

[3] Isaiah 66, 13.

[4] Isaiah 49, 15.

[5] Hosea 13, 8.

[6] Isaiah 42,14.

[7] Isaiah 66,13.

[8] Job 38,29.

[9] Luke 13,34.

[10] St. Bede, Commentary on the Books of the Old and New Testaments. On Proverbs. Electronic resource.

[11] St Augustine of Hippo, Opera omnia. Vol 2. On Genesis, Aleteia, Saint-Petersburg, 2000, p. 334.

[12] Carolyne Walker Bynum, Jesus as Mother. Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle Ages, University of California Press, Ltd., London, 1982 p. 111.

[13] Ivi, pp. 113-114.

[14] C.G. Jung, Psychologie und Religion, Gesammelte Werke, 8, Patmos-Walter, Düsseldorf 2011, p.132.

[15] C.G. Jung, Psychologie und Religion, Gesammelte Werke, 11, Patmos-Walter, Düsseldorf 2011, p. 137.

[16] Erich Neumann, La Grande Madre. Fenomenologia delle configurazioni femminili dell’inconscio, Casa Editrice Astrolabio, 1981, p. 20 In this sense, perhaps, our work of comparison with Thomism has something of phenomenological reading as well.

[17] Neumann, p. 25.

[18] As metaphor is a type of analogy, for the purposes of our study these two terms are interchangeable.

[19] Ivi, p. 27.

[20] Neumann, p. 35.

[21] Neumann, p. 51.

[22] Ivi, p. 213.

[23] Neumann, p. 63.

[24] Ivi, p. 41.

[25] Ivi, p. 39.

[26] To avoid terminological confusion, we will try to mostly use Latin words, as they appear in both the texts of Aquinas and in Fabro.

[27] Fabro lived and worked in the 20th century, largely interested in the contemporary and modern thought. His main influences include Hegel, Kierkegaard and Heidegger.

[28] For details on this aspect see Basti, ch. 5.4.2. Nozione di sostanza e categorie.

[29] Christian Ferraro, La svolta metafisica di San Tommaso, Lateran University Press, Città del Vaticano, 2014, p.39.

[30] The ‘being’ as everything that ‘is’ = that ‘exists’, both really and in way of merely logical conception (a condition of blindness can be even if it denotes the absence of something and strictly speaking, does not have its own ‘being’).

[31] Of all that is actualized, that has esse.

[32] In metaphysics cause’ is that which influences upon something positively and effectively, making it in some way dependent upon itself.

[33] That which makes the essence contract the esse.

[34] This would be the patriarchal archetypical reading of ontology; whereby female generative capacity is more akin to the matter that gives birth only when it receives the ‘spiritual’ (or ‘formal’ in the language of metaphysics) principle that orders it. Therefore, God, being immaterial and perfectly spiritual, is more logically called Father. However, as we have seen in the interpretation of Neumann, the transformative principle of the archetype of the mother does not act in the manner of the shapeless abyss, but itself serves as the ordering, ‘forming’ principle.

[35] That is, by determining itself into different degrees of being. So, like the archetype of Great Mother it manages to make the transformation and the generation occur from within itself, while containing everything that is transformed.

[36] S.Th., I, q.4, a.3, ad 3.

[37] It doesn’t become anything, it just is.

[38] Gianfranco Basti, Filosofia della Natura e della Scienza – I, Lateran University Press, Città del Vaticano, 2002, p.363.

[39] The significant analogical divergence with the phenomenological perspective can be found here. Depending on the reading that we give it, the Great Circle may itself coincide with the totality (more similar to pantheism), whereas in Fabro-Aquinas the transcendental participation makes the totality dependent on the formal Principle (more similar to panentheism).

[40] Christian Ferraro, La svolta metafisica di San Tommaso, Lateran University Press, Città del Vaticano, 2014, p. 32.

[41] De Causis, prop. 4 (cit. Ferraro, 2012, p. 213).

[42] Luke 14,9-10.

[43] Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy, Paradise, XXXIII, 1.

[44] Galatians 4,4.

[45] S.Anselm, De conceptu virginali et de originali peccato, ch. 18.

[46] See Table 2 in the Atachments for comparison of key concepts of both perspectives.

[47] Neumann, 35

[48] S.Th., I, q.4, a.3, ad 3.

[49] Ivi, p. 39.

[50] That is, by determining itself into different degrees of being. So, like the archetype of Great Mother it manages to make the transformation and the generation occur from within itself, while containing everything that is transformed.